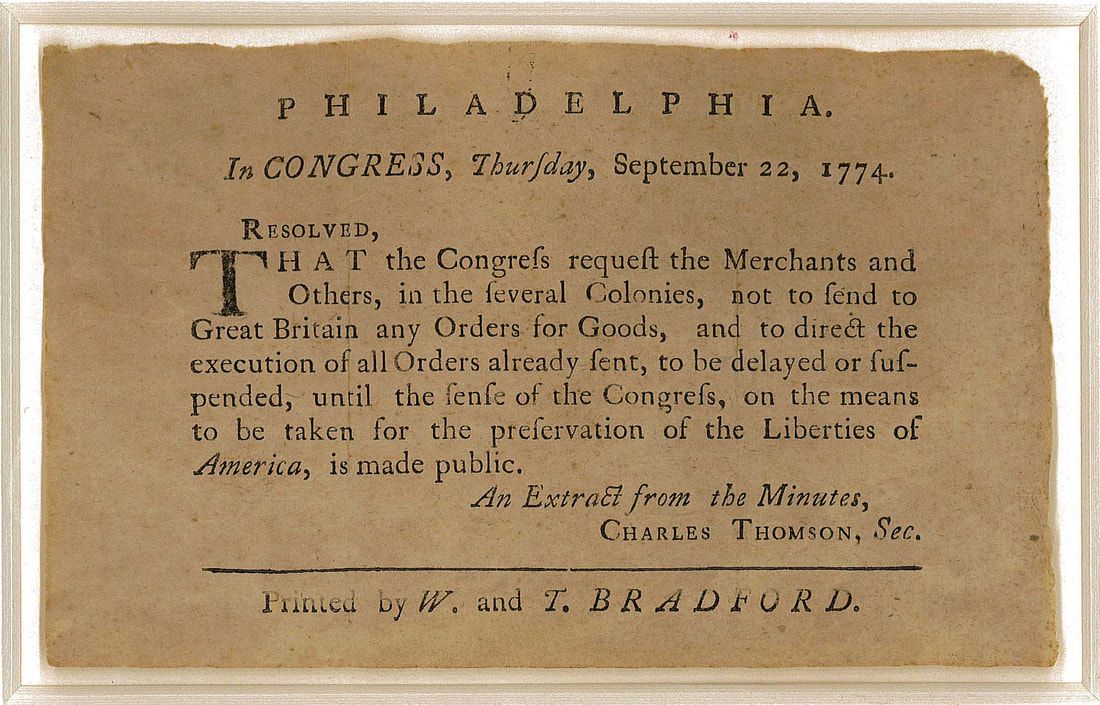

Wax Portrait of George Washington

Title: Wax Portrait of George Washington

Maker: Patience Wright [1725-1786]

Date: 1785-1786

Medium: Wax

Measurements: 20 ½” [H], 15 ½” [W], in oval frame

Provenance: Bequest of Albert H. Atterbury

Object ID: 1956.002.001

Credit Line: The Old Barracks Museum

This white wax portrait of General George Washington [1732-1799] shows him in his uniform in profile. The portrait is attributed to Patience Wright and is one of her last known completed works. Wright, a Quaker from Bordentown, NJ, was widowed in 1769. Having taught herself to sculpt using bread dough and wax, she supported her family by selling her wax artworks. Using her social connections, Patience moved to London in 1772 and continued sculpting wax portraits of political and military figures. She passionately believed in the ideals of liberty and wanted to create sculptures of those who fought for it, including George Washington. While Wright never met Washington in person, her son, Joseph Wright [1756-1793] sketched the general from life, and Patience based her sculpture on his work.

The first known owner of this Washington portrait was Elias Boudinot [1740-1821]. Trained as a lawyer, Boudinot was active in revolutionary politics. He served in New Jersey’s Provincial Assembly in 1775, in 1777 he was appointed the first commissary general for prisoners, and he was twice elected to represent New Jersey in the Continental Congress. His will describes a “bust of General Washington in white wax” being bequeathed to his relative Lewis Atterbury, who in turn gave it to his son Edward J.C. Atterbury, who then gave it to his son, Albert H. Atterbury. In 1956, Albert H. Atterbury donated the portrait to the Old Barracks Museum.

Additional Resources

This is one of five known wax portraits of George Washington attributed to Patience Wright. The others include:

The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts

National Park Service, Morristown National Historical Park

The John Jay Homestead

Mount Vernon: [attributes it to Joseph Wright]